Commentary

What I know of hākari is that its primary meaning is the use of gatherings and feasts as a way of displaying hospitality and mana. Over time, particularly in the 19th century, hākari started to include gratuitous – perhaps competitive – displays of wealth and excess. My reaction to this aspect of hākari was, honestly, surprise and distaste, although this is tempered by what I know of recent efforts to make hākari healthier.

As an environmentalist, I could not overlook the connections between excess consumption and environmental damage. I needed to incorporate this into my work.

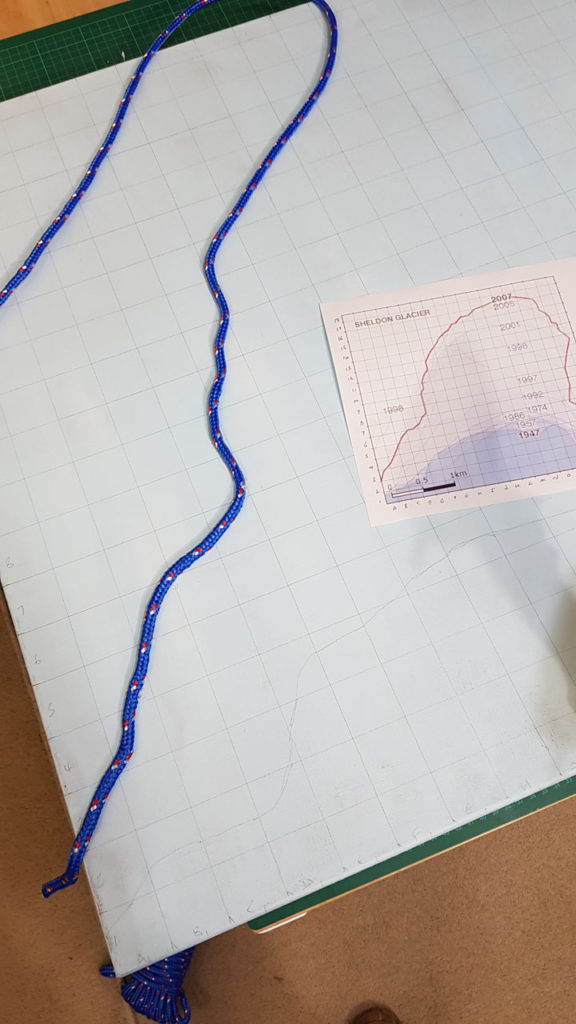

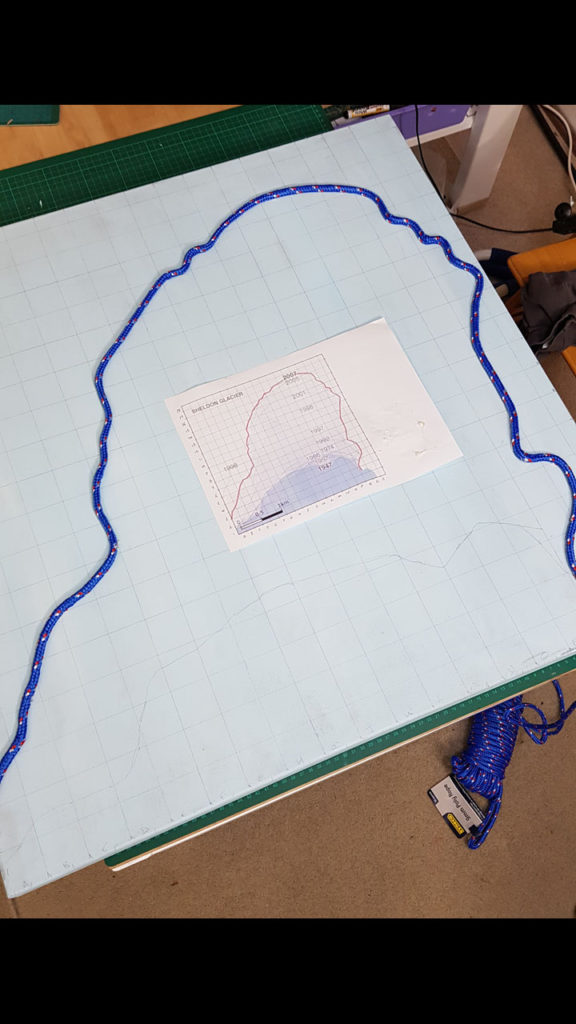

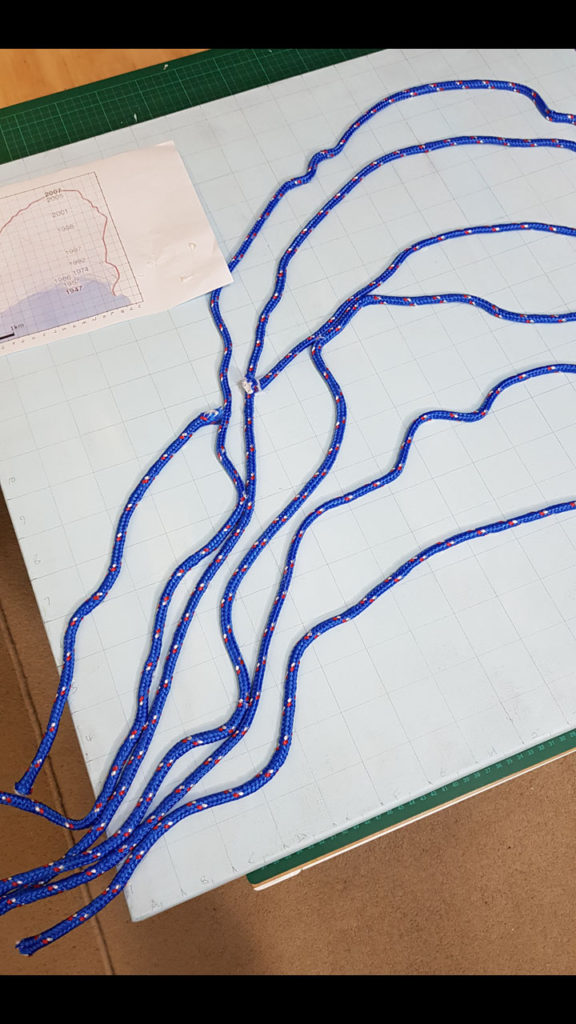

My piece is based on the effects of anthropogenic climate change in Antarctica. Looking at the available imagery, I became interested in the Sheldon Glacier and the shapes formed by its retreating front edge over the past several decades. Detailed mapping of the glacier shows that it has gradually retreated several kilometers from its original extent, each year moving back a little further, and forming a series of nested lines when viewed as a single image.

There is an element of hākari here too – a cyclicity in Nature as the glacial front ebbs and flows through the seasons and years.

Making of

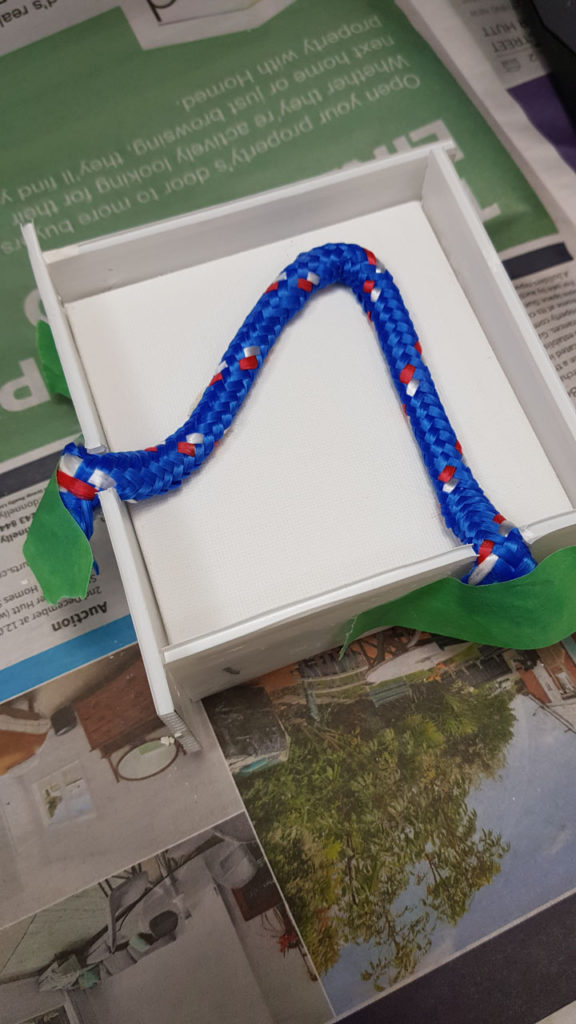

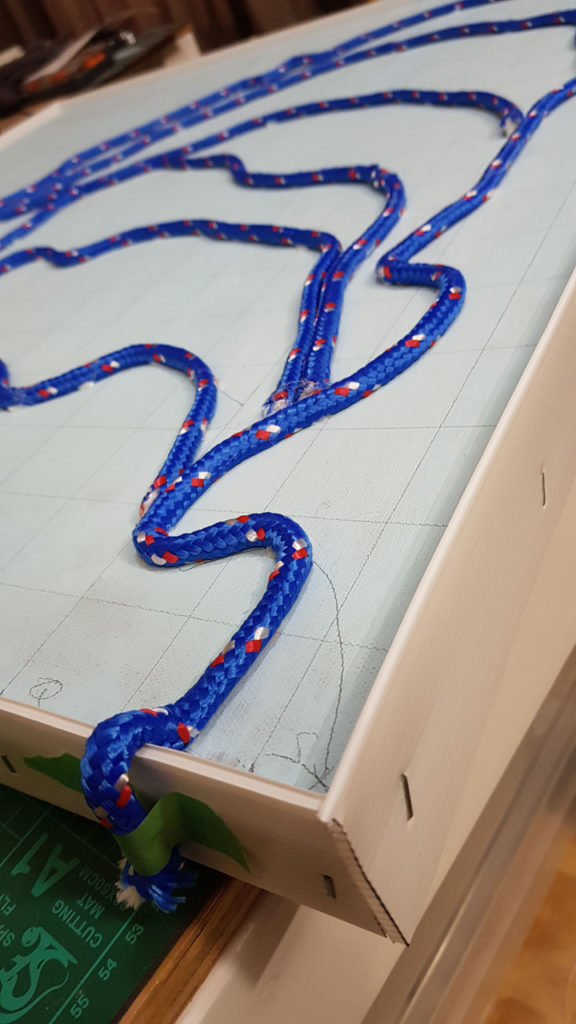

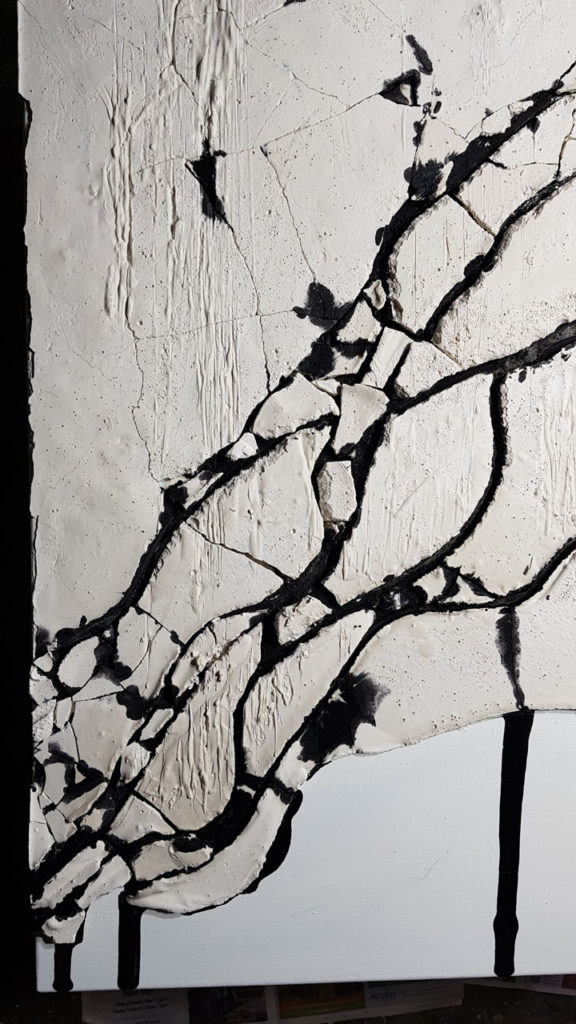

I took inspiration from Mark Bradford’s use of embedded ropes pulling through a surface to disrupt it. Rather than Bradford’s layers of paper, I instead experimented with plaster, which gave a suitably fragmented and torn effect, like broken sea ice.

In the final work, having the plaster on a canvas support allowed it to flex and crack, which is what I was hoping for based on previous experiments using a rigid base.

I wanted to highlight the resultant cracks and splits, and it felt right to use a carbon-based “sumi” ink to do this, representative of global carbon emissions. The ink was dripped into and across the disrupted areas of the piece.

The prototype

Scaling up

Final Work

Details

The work in context